Joi 17.11.2011 (toata ziua) si vineri 18.11.2011 (dimineata), a avut loc la Cluj stagiul de instructori al Fundatiei Romane de Aikido Aikikai. Lectiile au fost conduse de Dorin Marchis sensei, presedintele si directorul tehnic al organizatiei noastre. Au fost prezenti numerosi instructori si instructori asistenti, de la aproape toate dojo-urile din tara.

De joi dupa masa si pana duminica dimineata a avut loc stagiul de iarna al FRAA, in aceeasi locatie din Cluj.

Voi reveni cu detalii si informatii suplimentare.

luni, 21 noiembrie 2011

duminică, 13 noiembrie 2011

Stagiu al Federatiei Romane de Aikido Modern

Am avut onoarea si placerea de a fi invitat astazi, pentru a tine o lectie de o ora, la stagiul Federatiei Romane de Aikido Modern, organizat la dojo-ul maestrului Mihai Dulapciu. Au predat cate o lectie si alti maestri de Aikido, membri ai acestei organizatii si anume Serban Derlogea sensei, Ioan Grigorescu sensei si Alexandru Poteras sensei.

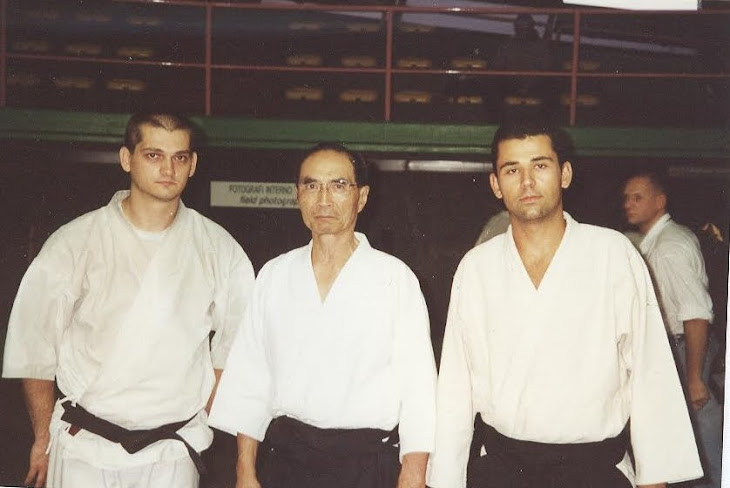

A fost o buna oportunitate de a-i revedea pe unii dintre prietenii mei si trebuie sa il mentionez aici, in afara celor mentionati mai sus, pe Marius Ionita sensei ) si de a transmite Aikido-ul scolii Aikikai, asa cum am reusit eu sa il percep pe la maestrii de la care am avut posibilitatea de a studia si in special, de la maestrul Fujita Masatake.

Sunt convins ca si in viitor vom mai avea ocazia de a ne reintalni pentru practica si doresc sa multumesc organizatorilor inca o data pentru aceasta invitatie.

|

| Uke : Valentin Paun, Kenshin dojo |

|

| Impreuna cu Serban Derlogea sensei |

A fost o buna oportunitate de a-i revedea pe unii dintre prietenii mei si trebuie sa il mentionez aici, in afara celor mentionati mai sus, pe Marius Ionita sensei ) si de a transmite Aikido-ul scolii Aikikai, asa cum am reusit eu sa il percep pe la maestrii de la care am avut posibilitatea de a studia si in special, de la maestrul Fujita Masatake.

Sunt convins ca si in viitor vom mai avea ocazia de a ne reintalni pentru practica si doresc sa multumesc organizatorilor inca o data pentru aceasta invitatie.

sâmbătă, 12 noiembrie 2011

Seminar aniversar Ramnicu Valcea

|

| Impreuna cu Serafim Stefan sensei si Sorin Despa Sensei |

|

| Uke : Danut Vatamanu, Tenchi dojo |

|

| Uke : Danut Vatamanu, Tenchi dojo |

Fara practica nu cred ca poate exista cu adevarat Aikido, sau cel putin nu in sensul in care il vad eu. Imi revin in minte cuvintele maestrului Fujita care, acum multi ani, intrebat fiind cum este ki-ul ne spunea intotdeauna acelasi raspuns : practicati, practicati, practicati. La acel moment marturisesc ca eram frustrat de acest (acelasi) raspuns insa cu trecerea anilor frustrarea aproape ca a disparut. Uneori raspunsurile nu sunt oferite prin cuvinte ci trebuie sa fie revelate fiecaruia de practica repetata, asidua. Astazi ma gasesc in situatia de a raspunde la fel unora dintre elevii mei si de fiecare data imi revine in minte figura maestrului.

Stefan Serafim sensei isi continua munca dedicata de promovare a Aikido-ului in Valcea si trebuie sa mentionez respectul deosebit pe care il am fata de aceasta perseverenta si capacitate de efort, pentru ca nu este usor ca opt ani sa parcurgi drumul de la Bucuresti la Valcea si retur, pentru a preda Aikido. Eu nu stiu daca as fi putut face asta, o spun cu mare sinceritate si cred ca este corect sa ii acordam tot creditul maestrului Serafim.

Sincere felicitari !

miercuri, 2 noiembrie 2011

Echilibrul - Balance, Eseu pentru shodan - Essay by, Valentin Paun

Natura nu cunoaste binele sau raul, frumosul sau uratul, ea este pur si simplu, fara extreme, fara directii sau valori absolute. Ea, natura, sau Universul (puteti sa-i spuneti si Dumnezeu, Buda sau Allah) este pur si simplu in echilibru. Acest echilibru, aceasta stare a punctului zero, atat de necesara pentru ca natura sa fie nemuritoare se afla, conform principiului hologramei in orice parte, fenomen sau subsistem al naturii.

Toate artele martiale cauta echilibrul insa fac acest lucru cu pasi mici. Si toate incearca sa gaseasca masura perfecta atat pe plan fizic cat si in plan spiritual.

Aikido, nefacand exceptie de la regula si fiiind o esenta a artelor martiale, incepe de la prima lectie prin invatarea echilibrului. Tehnicile din aikido au la baza dezechilibrul adversarului urmat de aruncarea, sau fixarea lui.

Din punctul meu de vedere, calea armoniei din aikido poate fi foarte bine inlocuita-echivalata cu calea echilibrului. Cele mai bune tehnici sunt cele in care dezechilibrul este perfect. In acel moment greutatea adversarului aproape nu mai exista iar partea urmatoare a atacului vine natural, fara efort ca un continuum de energie ce nu mai poate fi oprit.

Daca in cadrul celorlalte arte martiale dezechilibrul apare mai putin accentuat la finalizare, aikido il foloseste de la inceputul pana la sfarsitul fiecarei tehnici. Fiecare om indiferent de masa lui, mare, sau mica, poate fi dezechilibrat atunci cand este in miscare. Este foarte important ca atacul lui Uke sa fie cat mai cinstit cat mai real(natural). Fiecare om poate fi incadrat intr-o sfera, iar fiecare sfera are, in mod evident un centru. Acest centru este centrul de echilibru maxim al acelui om. Pentru al dezechilibra trebuie ca centrul nostru, al sferei in care ne incadram sa fie mai jos decat al lui. De aceea cand aplicam tehnicile de aikido coboram intotdeauna centrul nostru de greutate mai intai.

Oamenii sunt sensibili la dezechilibrarea fizica. De fapt sunt sensibili la orice fel de perturbare a echilibrului fie el fizic, mental sau de alta natura, ca sa nu mai vorbim de faptul ca sunt multi oameni care au rau de miscare. Ca exemple putem evidentia starea de rau pe care o au multi oameni atunci cand se afla intr-o ambarcatiune si datorita tangajului percep acut un rau fizic, sau, starea pe care o incercam la inaltimi foarte mari si care este de fapt nu un rau fizic ci un dezechilibru mental produs de teama..

In momentul unui atac mintea adversarului se focuseaza pe regasirea echilibrului, in parte datorita antrenamentului dar mai mult datorita capacitatii naturale a oricarei fiinte de autoconservare. Insa aici autoconservarea manifestata ca gest reflex este in mod vadit un handicap. Uke trebuie dezechilibrat atat fizic cat si psihic. Atunci cand el este fie un adversar foarte foarte puternic, sau un incepator, el va alege un atac asupra unui punct, maini, gat puncte sensibile si va apuca, sau lovi, punctul ales atat cu mintea cit si fizic. In functie de cat de priceput este dar si in functie de atac va ajunge sau nu la tinta.

Dupa inceperea atacului, simpla ridicare a bratelor in dreptul ochilor, sau un sabaki, unul dintre tenkan-uri va crea un dezechilibru mental, care chiar daca nu este vizibil fizic, va exista pentru un timp foarte scurt. Pentru a se redresa psihic si a incepe un alt atac, va dura un timp in functie de adversar, moment in care Tori va face tehnica.

Orice pozitie nenaturala a lui Uke sau a lui Tori duce la dezechilibru. Pozitia in aikido este naturala, cu o stabilitate buna, dar nu extrema ca in cazul altor arte martiale, unde pozitiile sunt joase si foarte stabile, dar rigide ne permitand miscarea corpului simultan cu a membrelor. Pozitiile si deplasarile unui aikidoka sunt simple si permit miscari foarte rapide fara eforturi fizice mari.

Putem afirma fara sa gresim ca echilibrul, exprimat in filozofia, disciplinele mentale si artele martiale asiatice este pentru aikido punctul central. Comuniunea cu adversarul, exprimata prin miscarea impreuna cu el pana la un punct de despartire ne arata simplu si eficient si o filozofie sanatoasa de viata conform expresiei grecesti - Panta rei - Totul curge, nimic nu rămâne neschimbat.

Nature knows no good or evil, no beautiful or ugly, it is as simple as it sounds, not extreme, without directions or absolute values. She, The Nature or The Universe (you can also say God, Buddha or Allah) is always in simply balance. This balance, this state of zero, so necessary for nature to be immortal, is - according to the hologram principles - in any part, phenomenon or subsystem of the nature.

All martial arts are looking for balance, but they do it using small steps. And they are all trying to find the perfect measure on both levels: physical and spiritual.

Aikido, making no exception from this rule and being an essence of martial arts, starts from the first lesson with learning the balance. The techniques of Aikido are based on unbalancing the opponent followed by throwing, or fix it.

From my point of view, the way of harmony from aikido can be substituted / equivalated with the way of balance. The best techniques are those in which unbalance is perfect. At that moment, there is almost no weight of the opponent and the next part of the attack comes naturally, without effort, as a continuum of energy that cannot be stopped.

If in other martial arts the imbalance is less pronounced at the end of the techniques, aikido uses the imbalance from the beginning to the end of each technique. Every man, regardless of his weight, big or small, can be unbalanced when is moving. It is very important that Uke's attack has to be as honest, as real (natural) as possible. Everyone can be framed in a sphere, and each sphere has obviously a center. This center is the center of the maximum balance of that man. To unbalance him, we need to have our center - the sphere in which we fit - to be lower than his. Therefore when we apply the techniques of aikido, we always lower our center of gravity first.

People are sensitive to physical imbalance. In fact they are sensitive to any disturbance of balance whether physical, mental or otherwise, not to mention the fact that there are many people who have motion sickness. For examples we can highlight the malaise that people have when they are in a boat and because of the pitch they perceive an acute physical harm, or the state that we face at very high altitudes which is not actually a physically harm but a mental imbalance as a result of the fear ..

When an attack comes, the opponent's mind focuses on finding the balance again, partially due to training but more due to natural capacity for self-preservation of any beings. But here, self-preservation manifested as reflex is obviously a handicap. Uke must be unbalanced both physically and mentally. When he is either a very strong opponent or a beginner, he will choose an attack on one point, hands, neck, sensitive points and he will grab, or hit the chosen point, with both the mind and the body. Depending on how skillful he is and also based on the type of attack, he will reach or not to the target.

After starting the attack, the mere lifting of the arms in front of the eyes, or sabaki, or one of tenkans will create a mental imbalance, which even if not physically visible, it will exist for a very short time. In order to recover mentally and start another attack it will take a while, depending on the opponent, moment in which Tori will execute the technique.

Any unnatural position of Uke or Tori lead to imbalance. The position in aikido is natural, with good stability, but not extreme as in other martial arts, where positions are low and very stable but rigid and not allowing body and limbs movement in the same time. Postures and movements of an aikidoka are simple and allow very quick movements without great physical effort.

We can affirm without mistake that the balance expressed in philosophy, mental discipline and Asian martial arts is the central point of aikido. Being one with the opponent, expressed by moving along with him to a point of separation shows us simple, efficient and a healthy philosophy of life according to Greek expression - Panta rei - everything flows, nothing stays the same.

English translation by Cristian Vlaescu. Many thanks

English translation by Cristian Vlaescu. Many thanks

Practica si timpul - Practice and time, Eseu pentru shodan - Shidan essay, Cristian Vlaescu

“Ce centura ai? De cat timp faci aikido?” Sunt intrebari atat de familiare, pe care aproape ca am ajuns sa le astept de la cei carora le spun ca practic aikido. Daca pentru prima intrebare raspunsul apare imediat (uneori nici nu este rostita din simplul fapt ca centura este la vedere), pentru cea de a doua intrebare, raspunsul meu sincer este la fel de prompt: Nu stiu!

Au trecut ani, ani buni, de la primul meu antrenament. Au trecut ani in care intensitatea practicii nu a fost mereu aceeasi. Au fost perioade in care am mers zilnic la antrenament, au fost perioade in care abia reuseam sa merg o data pe saptamana si au fost chiar saptamani in care nu am ajuns deloc, la nici un antrenament; am participat la antrenamente mai intense fizic, de la care plecam foarte transpirat, au fost si antrenamente mai putin intense, in care aratam incepatorilor tehnicile, si au fost chiar antrenamente la care am participat doar de pe banca, privind.

Refuz sa trag linie si sa adun, pentru a da un raspuns matematic de genul x ani si y luni. Refuz sa cred ca raspunsul la intrebarea “De cat timp faci aikido?” poate ajuta pe cineva sa se hotarasca daca va continua sa vina sau nu la antrenamente.

Intr-adevar, exista cateva metrici pe care le-as putea lua in considerare. Stiu cand am participat prima data la un antrenament de aikido deci stiu cat timp a trecut de la primul antrenament. E mai difici, insa daca insist suficient de mult cred ca as putea face un calcul pentru a spune la cate antrenamente am participat in total sau cate de ore de antrement reprezinta ele insumate. Cu o marja de eroare foarte mica as putea spune si la cate stagii am participat. Stiu foarte bine cate examene de aikido am sustinut si stiu cate din aceste examene le-am trecut. Acestea sunt masuratori ce ar putea oferi oarecare informatii despre “volumul” efortului depus.

Ceea ce nu se poate vedea din aceste masuratori este calitatea efortului. Metricile de mai sus nu reflecta atentia, gradul de implicare, numarul de dojo-uri de care am apartinut, numarul de sensei pe care i-am avut ca indrumatori, ce pregatire au avut, cat de buni au fost ei ca profesori si cat de bine am putut eu absorbi invataturile de la senseii “mei”. De asemenea, metricile nu ofera nici o informatie legata de absentele de la antrenamente, daca sau cat de bine intemeiate au fost motivele absentelor si nici daca au fost perioade mai lungi de absenta continua sau daca am participat intr-un ritm mai rar dar constant la antrenamente. Nu reflecta cat de bine am lucrat cu alti aikidoka, cat de bine ne-am inteles, cat de sincere au fost atacurile noastre si cat de corect am incercat sa executam tehnicile atunci cand lucram impreuna.

Observ ca pe masura ce detaliez, gasesc in metricile bazate pe timp mai multe apecte care nu se pot deduce fata de cele care se pot calcula. Nu contest faptul ca metricile pot oferi cateva informatii, insa cu siguranta nu par a fi informatiile cele mai utile in a afla timpul necesar pentru a ajunge la un anumit nivel de pregatire.

De-a lungul timpului, fiecare om trece printr-un proces de transformare. Fiecare isi defineste directia si fiecare stie daca merge sau nu in directia potrivita. Aikido este o cale. Nu este o cale universala, nu este a tuturor, insa este o cale care se pare ca dobandeste din ce in ce mai multi adepti. Este o cale pe care si eu am ales-o.

Inainte de a veni la primul antrenament de aikido, am cazut cel putin o data. Si m-am ridicat. Si-am mai cazut o data. Si iar m-am ridicat. La primul antrenament de aikido am facut exact acelasi lucru: am cazut si m-am ridicat, de multe ori. Inainte de a veni la primul antrenament de aikido, aveam niste principii de viata. Si am descoperit ca in colectivul de aikidoka nu numai ca le pot pastra ci chiar le pot intari.

De aceea, pentru intrebarea “De cat timp faci aikido?” prefer sa-mi pastrez raspunsul: Nu stiu. Poate ca din totdeauna, doar ca la un moment dat am realizat ca asa se numeste.

"What belt do you have? For how long are you practicing aikido?" These are questions that become so familiar that I almost come to expect them from those which I tell them that I practice aikido. If for the first question the answer rises instantly (and sometimes is not even uttered for the simple fact that the belt is in sight), to the second question, my honest answer is also straight: I don't know!

Years have passed, many years, since my first practice. There were years in which the intensity of practice was not always the same. There were times when I went to practice every day, there were periods in which I could only go once a week and there were even weeks when I did not practiced at all; I've participated to some trainings which were more physically intense, from which I left very sweaty, there were also less intense training, in which I showed the techniques to beginners, and there were even trainings which I attended only sitting on the bench and watching.

I refuse to draw a line and add, for giving such mathematical answer like x years and y months. I refuse to believe that the answer to the question "For how long are you practicing aikido?" can help someone to decide whether or not to continue to participate to trainings.

Indeed, there are some metrics that I can consider. I know when I first attended to an aikido training so I know how much time has passed since the first training. It's more difficult but if I insist I guess I could make a calculation to tell how many trainings I attended in total or how many training hours represent. With a very good approximation I could say to how many stages I've participated. I know very well to how many aikido exams I've participated and I know which of these exams I've passed. These are measurements that could provide some information about the "volume" of the effort.

What cannot be seen from these measurements is the quality of the effort. The above metrics do not reflect attention, involvement, number of dojos that I belonged, number of sensei that I had as teachers, what training they had, how good were they as teachers and how well was I able to absorb the teachings of "my" Sensei. Also, the metrics do not offer any information related with absences from training, if or how well-founded were the reasons for absences or whether there were long periods of absence or if I participated at a rarely but constant rate to the trainings. It does not reflect how well we worked with other aikidoka, how well we understand each other, how honest our attacks have been and how rigorous were we when we tried to execute the techniques while working together.

I see that while I'm going deeper, I find in time-based metrics more aspects that cannot be deduced then those that can be calculated. I do not deny that metrics can provide some information, but certainly do not seem to be the most useful information to find the necessary time for reaching a certain level of training.

Over time, everyone goes through a transformation process. Each defines its direction and each knows if it walks or not in the right direction. Aikido is a path. It is not a universal path, not for all, but it is a path that seems increasingly acquired by more followers. It is a path which I've chosen.

Before coming to the first aikido training, I fell at least once. And I got up. Then I fell again. And again I got up. At the first aikido training I did the same thing: I fell and got up for many times. Before coming to the first aikido training, I had some principles of life. And I discovered that inside the aikidoka team I can not only preserve but also can strengthen.

Therefore, for the question "For how long are you practicing aikido?" I prefer to keep my answer: I do not know. Perhaps for how long I know myself, just that at some time I realized that is called like this.

Impresii dupa examinare - Impressions after examination, Cristian Vlaescu, shodan

Imi plac examenele, chiar si atunci cand nu sunt eu cel examinat si particip doar ca uke, pentru ca sunt cele mai intense antrenamente. De data asta, fiind si eu printre cei examinati, chiar ma asteptam sa fie solicitant. Si a fost.

Nu stiu cum s-a vazut din public, dar stiu ca de pe tatami am simtit tensiunea. Am simtit cum se combina incarcatura emotionala cu efortul fizic. Am simtit cum ma comport atunci cand creste ritmul cardiac iar momentul de pauza nu mai vine. Si am simtit cum la un moment dat, o parte din mine a incetat sa mai functioneze. Iar ce m-a impresionat cel mai tare este ca in acele momente, desi nu nimeream intotdeauna pe procedeul cerut de sensei, am reusit sa-mi pastrez atitudinea de luptator, sa evit atacul si sa execut o alta tehnica. A urmat apoi Ju-Waza. Atacurile curgeau si imi doream sa execut alte tehnici, insa m-am surprins cum pe unele am inceput sa le repet. A fost si atacul celor 3 adversari, iar spre final, ping-pong-ul caderilor.

Interesant, cand m-am uitat la sfarsit, am vazut ca totul n-a durat decat un ceas.

Stiu, am vorbit cam mult despre mine, insa n-am apucat sa vad mare lucru despre altcineva. Multumesc colegilor cu care am lucrat si sper sa lucram in continuare la fel de bine, poate chiar mai bine, pentru a trece peste obstacolele pe care mi le-am descoperit in timpul examenului.

I like exams, even when I am not the examined one and I participate only as uke, because those are the most intense practice times. This time, being among those examined, I expected to be even more solicitant. And it was.

I don't know how it was seen from the audience, but I know that from tatami I felt the tension. I felt how the emotional charge combines with physical effort. I felt how I act when heart rate increases and break time is not coming. And I felt how at some moment, a part of me has stopped working. But what impressed me most is that in those moments, though I did not always fall on the techniques required by sensei, I managed to keep my attitude of a fighter, to avoid the attack and to apply another technique. After that, it followed Ju-Waza. Attacks flew and I wanted to execute other techniques, but I surprised myself how some of them began to repeat. Then was also the 3 enemies attack, and to end the ping-pong falls.

Interestingly, when I looked at the end, I saw that everything lasted only one hour.

I know, I've talked a lot about me, but I couldn't see too much about anyone else. I thank to colleagues with whom I worked and still hope to work as well in the future, perhaps better, to overcome the obstacles that I've discovered during the exam.

marți, 1 noiembrie 2011

Examinari - Exams

In 26.10.2011 am examinat pe cativa dintre practicantii de la Kenshin dojo. A fost un examen bun si toti cei examinati au promovat. Din aceasta data Kenshin dojo are doi noi yudansha : Valentin Paun si Cristian Vlaescu.

Felicitari tuturor !

I examined some of Kenshin dojo practitioners on October 26, 2011. It was a good exam and all the examinees were promoted. From this date on Kenshin dojo has two new yudansha : Valentin Paun and Cristian Vlaescu.

Congratulations to all !

Multumiri catre George Stoian sensei (Kenshin dojo), Sorin Despa sensei (Tenchi dojo) si Nicolae Mitu sensei (Itsushin dojo) pentru asistenta. Lui Mitu sensei ii multumim si pentru faptul ca ne-a pus la dispozitie dojo-ul sau pentru examinare.

Thanks to George Stoian sensei (Kenshin dojo), Sorin Despa sensei (Tenchi dojo) and to Nicolae Mitu sensei (Itsushin dojo) for their assistance. We thank Mitu sensei for allowing us to use his dojo for the exam.

Felicitari tuturor !

I examined some of Kenshin dojo practitioners on October 26, 2011. It was a good exam and all the examinees were promoted. From this date on Kenshin dojo has two new yudansha : Valentin Paun and Cristian Vlaescu.

Congratulations to all !

Multumiri catre George Stoian sensei (Kenshin dojo), Sorin Despa sensei (Tenchi dojo) si Nicolae Mitu sensei (Itsushin dojo) pentru asistenta. Lui Mitu sensei ii multumim si pentru faptul ca ne-a pus la dispozitie dojo-ul sau pentru examinare.

Thanks to George Stoian sensei (Kenshin dojo), Sorin Despa sensei (Tenchi dojo) and to Nicolae Mitu sensei (Itsushin dojo) for their assistance. We thank Mitu sensei for allowing us to use his dojo for the exam.

Abonați-vă la:

Comentarii (Atom)